- Home

- ABOUT DR. YANNI

- SPINE DISORDERS

- General Information

- Anatomy of the Spine

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Bone Grafts

- Back and Neck Braces

- Diagnosing Spine Problems

- Epidural Steroid Injection (ESI)

- Osteoporosis

- Lifestyle Risk Factors

- Biological and Medical Risk Factors

- Preventive Treatment Options

- Possible Complications of Spine Surgery

- Pain Medications

- Post Surgery Rehabilitation

- Surgical After Care

- Spinal Injections

- Spinal Rehabilitation

- Radiological Imaging and Tests

- Cervical Spine

- Anterior Cervical Fusion

- Anatomy of the Cervical Spine

- Cervical Corpectomy and Strut Graft

- Cervical Fusion

- Cervical Kyphosis

- Cervical Laminectomy

- Cervical Radiculopathy

- Cervical Spinal Stenosis

- Neck Pain (Overview)

- Posterior Cervical Fusion

- Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Cervical Spine

- Rehabilitation of the Cervical Spine

- Artificial Disc

- Thoracic Spine

- Lumbar Spine

- Adult Scoliosis

- Compression Fractures

- Degenerative Adult Scoliosis

- Degenerative Disc Disease

- Intervertebral Cages

- Low Back Pain (Overview)

- Low Back Pain in Athletes

- Laminotomy and Discectomy

- Lumbar Herniated Disc

- Lumbar Laminectomy

- Lumbar Spine Anatomy

- Lumbar Spinal Fusion

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

- Lumbar Spine Surgery

- Possible Complications

- Pedicle Screws and Rods

- Rehabilitation for Low Back Pain

- Scoliosis

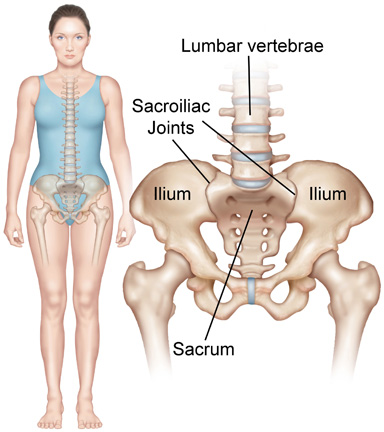

- Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome

- General Information

- For Patients

- Referring Physicians

- Practice Information

- Contact Us

- QUESTIONS? CALL US: (949) 515-0051

×

- Home

- ABOUT DR. YANNI

- SPINE DISORDERS

- General Information

- Anatomy of the Spine

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Bone Grafts

- Back and Neck Braces

- Diagnosing Spine Problems

- Epidural Steroid Injection (ESI)

- Osteoporosis

- Lifestyle Risk Factors

- Biological and Medical Risk Factors

- Preventive Treatment Options

- Possible Complications of Spine Surgery

- Pain Medications

- Post Surgery Rehabilitation

- Surgical After Care

- Spinal Injections

- Spinal Rehabilitation

- Radiological Imaging and Tests

- Cervical Spine

- Anterior Cervical Fusion

- Anatomy of the Cervical Spine

- Cervical Corpectomy and Strut Graft

- Cervical Fusion

- Cervical Kyphosis

- Cervical Laminectomy

- Cervical Radiculopathy

- Cervical Spinal Stenosis

- Neck Pain (Overview)

- Posterior Cervical Fusion

- Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Cervical Spine

- Rehabilitation of the Cervical Spine

- Artificial Disc

- Thoracic Spine

- Lumbar Spine

- Adult Scoliosis

- Compression Fractures

- Degenerative Adult Scoliosis

- Degenerative Disc Disease

- Intervertebral Cages

- Low Back Pain (Overview)

- Low Back Pain in Athletes

- Laminotomy and Discectomy

- Lumbar Herniated Disc

- Lumbar Laminectomy

- Lumbar Spine Anatomy

- Lumbar Spinal Fusion

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

- Lumbar Spine Surgery

- Possible Complications

- Pedicle Screws and Rods

- Rehabilitation for Low Back Pain

- Scoliosis

- Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome

- General Information

- For Patients

- Referring Physicians

- Practice Information

- Contact Us